To most folks, New Orleans naturally comes to mind as Mardi Gras approaches. To be immersed in a carnival of such profound excess must be something undoubtedly special. However, I confess to having only experienced that celebration vicariously as a viewer of the nightly news whenever Fat Tuesday rolls around each year. The New Year’s Eve that Sylvia and I celebrated in New Orleans with some friends years ago was great fun, but probably nothing like my imagined Mardi Gras parade where drunken revelers tear at their clothes and flail around in a Bacchanalian snake dance, strings of brightly colored beads flying everywhere.

For a while in the early sixties, my hometown Catholic high school would sponsor a “Mardi Gras” annual fundraiser. Beloit Catholic High bore little resemblance to New Orleans. The school gym, decorated in festive ribbons of crepe paper, featured an array of booths, each containing a cheesy carnival game like one you might have played at a country fair in the previous century. Food and baked goods were both sold and offered up as prizes. I remember parading around in a “cakewalk,” dutifully attempting to win some homemade sweets, confident my quarter entrance fee would positively impact the bottom line of the high school I’d be entering one day.

Mardi Gras wouldn’t be worth a hill of baked goods without music. But it wasn’t the saints marching in for this event. (Actual saints marching into a Catholic school would have been very cool, though.) Instead, I heard a band playing rock ‘n’ roll as I wandered down the hallway toward a large classroom that served as the school’s sole study hall. I wanted to be in that number. The room was packed, not with wild Bacchanalian revelers, but with mostly tame high school kids doing the twist. I paused for a second in the doorway, nodded to a couple of classmates from my grade school, then strode briskly to the front of a makeshift bandstand on which stood four guys in matching ties and vests, totally rocking out on two guitars, a bass, and drums.

They were Mic’s Masters and they were deep into an instrumental number I didn’t recognize. Three of them were swinging their guitar necks back and forth in time to the music. All at once, they broke into synchronized footwork that got them moving left to right and back again, wailing guitars swinging along with them. It was an impressive display of showmanship and one to which I immediately aspired.

I stood there mesmerized, listening to their set that included a spot-on cover of the Rivingtons’ Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow and some instrumentals that showed off their guitar chops. Mic’s Masters were the first rock ‘n’ roll band from Beloit to record in a small, private studio north of town and release a 45-rpm record containing two instrumentals. The A-side was a cover of Sandstorm by Johnny & the Hurricanes. The B-side, though, was their own composition, Rock-n-Round. Either would conjure up images of surfing in California over carousing in Louisiana.

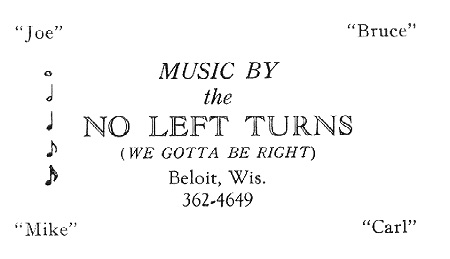

I won’t be parading through the French Quarter, carousing to the music of Professor Longhair or C.J. Chenier on Fat Tuesday this year either. Even if I was, the image of twisting to Mic’s Masters at that small-town fundraiser would remain indelibly etched in my mind. Beads or no beads, Bourbon Street or Beloit, you can bet I’ll let the good times (rock and) roll on Mardi Gras. Laissez les bons temps rouler!

(Special thanks to Jean Voss for graciously providing the Mic’s Masters memorabilia. Click on “Rock-n-Round” above for the full effect.)